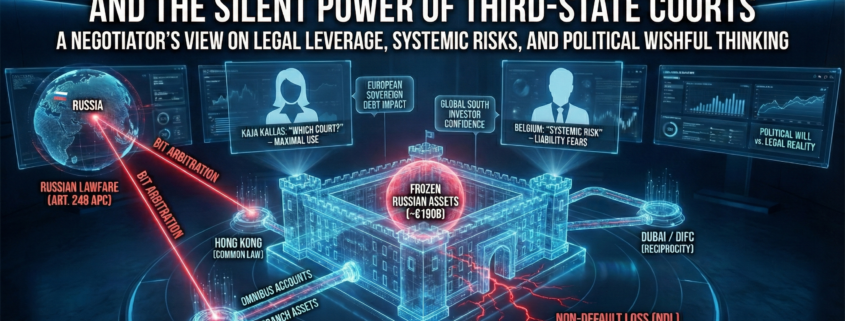

When Sanctions Backfire: Euroclear, Kallas and the Silent Power of Third-Country Courts

1. Why Euroclear Is Suddenly the Front Line of Geopolitics

From a negotiator’s perspective, the conflict over the frozen Russian central bank reserves is more than a technical sanctions dispute. It is a power struggle over who ultimately bears the expected “residual loss”: the EU member states, Belgium as the home state of Euroclear, or Euroclear itself as a systemically important financial market infrastructure. Kaja Kallas’s “famous” question – “Which court is Russia supposed to go to?” – suggests that Russia in practice has no effective legal remedies. Belgium, Euroclear and a growing number of practitioners, me included, see this very differently.

To understand why, we need to start with Euroclear’s ownership and functional structure.

2. Euroclear: Who Owns the “Plumbing” of the Global Financial System?

2.1 Ownership structure and role in the market

Euroclear is not a normal credit institution but the backbone of securities settlement. Euroclear Holding SA/NV in Belgium is the parent company and Euroclear Bank SA/NV is the operating bank based in Brussels, regulated by the National Bank of Belgium and embedded in EU regimes such as CSDR and EMIR. The majority shareholders are large financial institutions and market participants; in addition, there are national CSDs (for example Euroclear France and Euroclear Belgium) as group companies.

Euroclear Bank acts as an International Central Securities Depository (ICSD). It safekeeps securities with a volume of more than 40 trillion euros, processes bond, equity and fund transactions worldwide and provides collateral and cash management for banks, central banks and institutional investors. This makes Euroclear systemic: if something goes wrong here, it does not affect “a single bank” but the marketability of entire asset classes.

2.2 Global presence – and why Hong Kong and Dubai matter

Euroclear Bank SA/NV does not operate via separate legal subsidiaries, but through branches and representative offices. There is a branch in Hong Kong (a licensed bank under the supervision of the HKMA), further branches in places such as Krakow and Tokyo and representative offices in Dubai (DIFC), New York, Singapore and other locations.

The key point is that a branch is not a separate legal entity. The assets of the Hong Kong branch are assets of the Belgian Euroclear Bank SA/NV. An enforceable judgment against Euroclear can therefore in principle be enforced against branch assets in Hong Kong or other jurisdictions. This makes Hong Kong and, in a second step, Dubai interesting leverage points for third countries that do not support the EU sanctions architecture.

3. The Kallas Thesis vs. the Belgian Reality Check

3.1 Kallas: “Maximum use” – and the question “Which court?”

Since moving into the role of High Representative, Kaja Kallas has been the political figurehead of the “maximum use” line for the frozen Russian central bank funds. A significant share of the CBR reserves (around 185–190 billion euros) is held at Euroclear in Belgium. On this basis, a Ukraine “reparations loan” of around 140 billion euros is being constructed, economically “secured” by the immobilised reserves. Kallas argues under international law with the doctrine of countermeasures: a state that commits serious violations of international law cannot invoke full protection of its property in the same way.

Her notorious statement to EPP members of the European Parliament – in essence: “Which court is Russia supposed to go to? Which judge would ever rule in Russia’s favour here?” – is politically catchy at first glance, but in fact -ignores that Russia is no longer dependent on Western courts alone.

3.2 Belgium: “Fundamentally wrong” and “systemic risks”

Belgium, as the home state of Euroclear and its primary supervisory jurisdiction, is much more sober. Prime Minister Bart De Wever has described the Commission’s plans as “fundamentally wrong” and explicitly warned of systemic risks for the EU as a financial centre. Belgium sees two layers of exposure.

First, there is liability risk under the Belgium/Luxembourg–Russia BIT (1989), a bilateral investment treaty with classic guarantees against expropriation and unfair treatment. Second, there is balance sheet risk at the level of Euroclear itself, whose equity is in the single-digit billions while potential claims could be in the high double- or even triple-digit billions.

Belgium is therefore openly calling for EU-wide risk sharing and guarantees. Without a backstop provided by the EU, Euroclear would in practice become the solvency front line for a geopolitical decision taken in Brussels and Washington.

4. Anatomy of the Target: Balance-Sheet Logic, Omnibus Accounts and NDL Risk

4.1 The Russian “lump” in the Euroclear balance sheet

A single block now dominates the balance sheet of Euroclear Bank SA/NV. The total balance sheet amounts to around 220–230 billion euros, of which roughly 180–190 billion euros are immobilised Russian sovereign and central bank deposits. The interest earned on these deposits generates “extraordinary revenues” of several billion euros annually, which the EU now largely diverts to Ukraine.

From a negotiator’s point of view, this is not a side issue but a single point of failure in the bank’s balance sheet.

4.2 Omnibus structures: when one account holds thousands of investors

Many Euroclear positions in third countries are not held as segregated accounts, but via omnibus accounts at local central securities depositories or correspondent banks, such as the HKMA/Central Moneymarkets Unit, global banks in Hong Kong or Standard Chartered in the UAE. Legally, the underlying securities belong to the end investors, but at local account level they appear as a pooled position held in the name “Euroclear Bank”.

In an enforcement scenario, for example, a garnishment order against “all assets of Euroclear Bank in Hong Kong”, a court or a bank may initially attempt to block the entire balance until the individual ownership positions have been clarified. This is not automatic, but it is a pattern that has been observed in comparable custody situations. The consequence is that even a purely regional freeze in Hong Kong can temporarily shut down settlement for a large group of global clients – an operational heart attack before insolvency is even on the table.

4.3 Non-default loss: why legal judgments hit equity directly

Infrastructure regulation differentiates between two types of losses. Default loss is the loss from a participant default (for example a bank or broker). In such a case, waterfalls, margins and default funds apply. Non-default loss (NDL), by contrast, arises from other causes such as legal disputes, fraud or cyber incidents.

Judgments from Russian courts or arbitral awards based on the BIT clearly fall into the NDL category. They are not cushioned by default funds but flow directly through the profit and loss account and into equity. A damages award in the double-digit billions would clearly exceed the existing equity base and, without external recapitalisation, push Euroclear towards -technical insolvency. From a risk manager’s perspective, it is therefore almost inevitable that Belgium does not want to carry this burden alone.

5. Russia’s Lawfare: From a Moscow Judgment to a Global Lever

5.1 Article 248 APC – the “Lugovoy Law” as a legal weapon

With the introduction of Articles 248.1 and 248.2 of the Russian Arbitrazh Procedure Code in 2020, Moscow deliberately redrew the playing field. Russian courts declare themselves exclusively competent when sanctioned Russian parties are involved, even in the face of explicit arbitration clauses or foreign jurisdiction clauses. The rationale is that sanctions prevent Russian parties from having effective access to justice in the West, making Western jurisdiction clauses ineffective. The courts can issue anti-suit and anti-arbitration measures and can forbid companies such as Euroclear from pursuing proceedings abroad.

5.2 Judgments as an export product

More than one hundred proceedings are now pending against Euroclear before Russian courts; several banks and investors have already been awarded damages. The logic runs in four steps.

First, Russia generates enforceable judgments against Euroclear.

Second, there are hardly any attachable Euroclear assets in Russia itself, because the relevant Type-C accounts are also blocked.

Third, the judgments are therefore exported to Hong Kong, Dubai and other jurisdictions. Fourth, claimants attempt to “translate” them into local law and enforce them against branch assets or receivables.

The EU has recognised this dynamic and, with its fifteenth sanctions package, explicitly prohibited the recognition and enforcement of Lugovoy-based judgments within the EU.

This deliberately shifts the conflict into third countries.

6. Hong Kong: FSIL, Common Law and the Real Lever Against Euroclear

6.1 What the Foreign State Immunity Law (FSIL) actually changes

With China’s Foreign State Immunity Law, which has been in force since 1 January 2024, China has moved from absolute to restrictive state immunity. States and state entities no longer enjoy immunity for clearly commercial activities and enforcement against state assets used for commercial purposes is eased.

For any sound argumentation, three clarifications matter. FSIL is aimed primarily at states and state-related entities, not at private banks. For Euroclear, FSIL is only indirectly relevant, for example if Belgium or EU bodies were sued or subjected to enforcement measures in Hong Kong. The direct attack vector against Euroclear itself runs via classic common-law judgment enforcement and garnishee orders, not via state immunity.

6.2 Recognition of Russian judgments: obstacle or door opener?

Hong Kong remains a common-law court system, even though Beijing’s political influence is increasing. For the recognition of foreign judgments without a specific treaty, three conditions apply: the originating court must have had jurisdiction under Hong Kong standards, the judgment must be final and conclusive and it must not clearly violate public policy.

At the same time, Hong Kong positions itself as a “sanctions-neutral” financial centre. EU and US sanctions do not apply automatically and the courts have in several cases stopped Russian anti-suit manoeuvres and upheld arbitration agreements, even against sanctioned Russian banks.

For Euroclear this means that a Russian judgment could be recognised in individual cases, but the courts will examine very carefully whether Article 248 judgments themselves are abusive or overly political.

6.3 Practical access: branch capital, clearing accounts, omnibus structures

If a judgment is recognised, three types of assets are in focus in Hong Kong: the regulatory capital of the Hong Kong branch, accounts at the HKMA and other clearing banks and receivables of Asian institutions against Euroclear for fees and settlement cash.

An aggressive court could, at least temporarily, freeze balances, reroute payment flows or block specific settlement functions in the enforcement process. That is enough to trigger -a significant regional shock in Euroclear’s Asian business, even if the core of the Russian central bank deposits in Belgium remains untouched.

7. Dubai / DIFC: Reciprocity as a Flexible Lever

7.1 Dual court system and “conduit” risk

Dubai has a dual court system. Onshore courts operate in Arabic under civil law, while the DIFC Courts are common-law courts in English with an international profile. The DIFC is often used as a conduit jurisdiction: first an overseas judgment is recognised in the DIFC, then this DIFC judgment is enforced in the rest of Dubai.

For Russian creditors this is attractive because many international banks and payment flows are routed through the DIFC and because UAE courts are increasingly willing to recognise foreign judgments on the basis of de facto reciprocity.

7.2 Real but not yet tested danger

There are as yet no publicly documented cases in which a Lugovoy-based judgment against a major Western financial institution has been enforced in the DIFC. The danger is therefore potential rather than already realised.

For Euroclear, Dubai nonetheless represents a non-negligible lever, because it maintains a representative office in the DIFC, cash clearing in the UAE is partly provided by Standard Chartered and Russian and Gulf capital flows increasingly intersect there.

A garnishable setup would be, for example, receivables of MENA banks against Euroclear, such as fee income or reimbursement claims, which could be redirected to a Russian creditor on the basis of a court order.

8. The Belgium/Luxembourg–Russia BIT (1989): The Quiet but Powerful Lever

The bilateral investment treaty between Belgium/Luxembourg and the USSR/Russia (1989) is still in force and offers protection against expropriation and measures equivalent to expropriation, a fair and equitable treatment standard, free transfer of capital and returns and investor–state arbitration as an escalation channel. For Russian investors whose assets have been immobilised in Belgium via Euroclear, this is a legitimate legal basis to sue Belgium for indirect expropriation or unfair treatment and a way to obtain compensation through an arbitral award, even if the original assets remain frozen.

This shifts the risk from Euroclear to the level of the Belgian state, which in turn faces political pressure to share this risk via EU-wide guarantees.

9. What Courts in Hong Kong and Dubai Can – and Cannot – Do

From a negotiator’s standpoint, some clarifications are crucial. Courts in third countries cannot overturn EU sanctions or Belgian legislation. They have no jurisdiction to end the blockade of CBR balances in Belgium directly. What they can do, however, is recognise Russian judgments or arbitral awards, enforce them against local Euroclear assets or receivables and place banks and infrastructures in their jurisdiction in a conflict between local court orders and EU sanctions law.

Hong Kong and Dubai are therefore not switches that can unlock the frozen assets, but they are –amplifiers of pressure.

They can -significantly weaken Euroclear regionally and increase the cost of the sanctions regime for Europe.

10. A Negotiator’s View: Strategic Lessons Learned

From a negotiator’s perspective, five hard lessons emerge.

First, the Kallas question is wrongly framed.

The issue is not whether “a Western judge” will rule in favour of Russia, but how many non-Western courts and arbitral tribunals will give Russia a stage.

That number is -significant.

Second, Euroclear is in practice the liability front line of the EU. The combination of a massive Russia exposure, NDL logic and global branch and omnibus structures makes Euroclear the operational carrier of a political project whose risks have so far only been partially socialised at EU level.

Third, BIT plus lawfare plus third-country courts equals structural permanent pressure.

The Belgium/Luxembourg–Russia BIT, Article 248 APC and possible recognitions in Hong Kong and Dubai together form a robust toolkit with which Belgium and Euroclear can be drawn into legal conflicts for years.

Fourth, the real switches sit in Brussels, not in Hong Kong or Dubai.

The political switch is the Council of the EU, which can amend or repeal sanctions regulations.

The legal switch is the General Court and the Court of Justice of the EU, which can annul such acts in whole or in part.

The operational valves are the Belgian authorities, which can grant licences. Euroclear and the courts of third countries operate only within this framework.

Fifth, without explicit EU guarantees, the Ukraine loan is a solvency race.

The further the EU moves from temporary immobilisation towards effectively -illegally-confiscating Russian assets, the more important binding liability commitments for Belgium and Euroclear become, as well as clear communication towards investors from the Global South and a realistic recognition of the fact that courts in third countries are not a footnote but an independent power factor.

Otherwise, the bill for Brussels’ questionable actions will once again..

Explode in the pockets of EU citizens.

ImpactNegotiating - 2025

ImpactNegotiating - 2025