Negotiation strategies are far from a “one-size-fits-all” solution; instead, they are profoundly shaped by our unique personalities and the array of experiences we accumulate over our lifetimes. Gaining an understanding of popular models of conflict and bargaining styles, such as those put forth by Thomas-Kilmann and G. Richard Shell, can greatly enhance our ability to navigate not only our own tendencies but also effectively influence those of our negotiation partners for the better.

Like the well-known Thomas-Kilmann model, Shell’s framework sorts negotiators into five primary styles: accommodating, compromising, avoiding, collaborating, and competing. Shell notes that individuals often display a mix of strong or weak preferences across these strategies, which significantly shapes their approach to bargaining in different contexts.

No single style ensures negotiation success; each comes with its own strengths and weaknesses. For example, accommodators are typically excellent at building relationships and tuning into others’ emotional cues—a significant advantage in negotiations. However, their focus on relationship maintenance may sometimes overshadow the more strategic aspects of negotiation, potentially making them vulnerable to more aggressively competitive tactics.

A frequent error in negotiation is the assumption that others share our styles, which can lead to significant misunderstandings and miscommunications. For instance, a competitive negotiator might view a cooperative counterpart’s openness as deceptive, potentially exploiting it, leading to conflict and feelings of betrayal.

To avoid such pitfalls, Shell suggests initiating discussions on less critical issues to carefully gauge counterparts’ styles. This tactic helps determine whether they lean towards cooperation or competition, allowing for better strategic adjustments without trying to change their inherent nature.

Despite the apparent rigidity of our natural negotiating styles, Shell asserts that we can enhance our negotiating effectiveness by adopting four key practices, all of which resonate with my personal experience:

Thorough preparation.

Setting ambitious goals.

Listening intently to gather crucial information.

Upholding the highest standards of integrity to maintain a strong reputation.

These habits can significantly refine the negotiation skills of individuals from any field, including those from high-stakes, competitive industries like Oil & Gas. Having undergone transformative education at institutions like Harvard, I’ve found these insights not only applicable but crucial in evolving my negotiation capabilities.

Conflict naturally arises from our interactions, as no two individuals have exactly identical expectations and desires. We can analyze an individual’s approach to conflict along two dimensions:

Assertiveness: How much a person tries to satisfy their own concerns.

Cooperativeness: How much a person attempts to accommodate the other’s concerns.

From these dimensions, we identify the five distinct conflict-handling modes, with each of us capable of employing any depending on the situation, yet often favoring certain modes over others due to our temperament and experiences.

Here’s a more detailed look into each mode to give you a clearer understanding of how they can be effectively utilized in various negotiation and conflict situations:

Competing: This mode is highly assertive and minimally cooperative, focusing on one’s own needs at the expense of others’. It is suitable for situations where decisive action is necessary, such as during emergencies or when urgent decisions need to be made. Competitors tend to take a firm stand, which can be effective when defending important issues but may lead to conflict if overused.

Accommodating: In contrast to competing, accommodating is highly cooperative but not assertive, prioritizing the other person’s needs over one’s own. This mode is useful when the issue matters more to the other person than to oneself, or when preserving harmony is more important than winning. While accommodating helps in maintaining relationships, excessive use might lead to being overlooked in decisions.

Avoiding: This mode involves neither asserting one’s own interests nor cooperating to satisfy the other’s. Avoiding can be effective when the stakes are low, or when more important issues need attention. It can also prevent unnecessary problems when time is needed to gather more information or cool down heated emotions. However, consistent avoidance might lead to unresolved issues accumulating.

Collaborating: Combining assertiveness and cooperativeness, this mode aims for a win-win situation where the needs of both parties are met. It is ideal for complex scenarios where both sides’ stakes are high. Collaborating involves understanding and integrating different viewpoints, which can lead to innovative solutions and strong partnerships.

Compromising: This mode is moderately assertive and cooperative, seeking a quick resolution that somewhat satisfies both parties. It is practical when a temporary solution is needed or when equal power dynamics prevent one side from dominating. Compromising can resolve conflicts efficiently by ensuring that all parties give and take somewhat, but it might not always be the most satisfying or enduring “root cause” solution as it often involves each party making concessions.

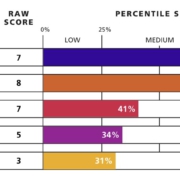

Finally, the picture for this post shows my own, actual TKI profile after thorough exploration of my conflict-handling styles through the Thomas-Kilmann Instrument. This assessment provides a nuanced view of how I tend to manage conflicts, showing a strong preference for accommodating and collaborating. This suggests I’am often considerate of others’ needs and strive for cooperative solutions, which can be highly effective in maintaining relationships and ensuring team harmony. My approach likely helps in creating an environment where all parties feel heard and valued, contributing positively to conflict resolution processes. Anyhow, the effectiveness of a given conflict-handling mode depends on the requirements of the specific situation and the skill with which you use that mode. I’am capable of using all five conflict-handling modes; I cannot be characterized as having a single, rigid style of dealing with conflict, or, to put it easy: It’s much about your developed levels of Adaptiveness! However, most people use some modes more readily than others, develop more skills in those modes and therefore tend to rely on them more heavily. Many have a clear favorite. The conflict behaviors I use are the result of both, my personal predispositions and the requirements of the situations in which I find myself.

Generally, a good understanding of conflict-handling styles can be a valuable tool in both, personal growth and professional development as well, aiding in better decision-making and relationship management across various situations.